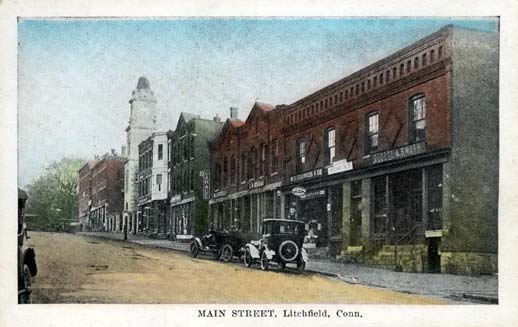

The recent centennial of the end of World War I provides a timely opportunity to look back on how that occasion was marked in Litchfield. The following account of November 11, 1918, is from Alain White’s 1920 book, The History of the Town of Litchfield, Connecticut, 1720-1920:

“The Court House bell gave the local signal and soon all the church bells

joined in, ringing out the tidings in a perfect medley of noise. The firemen manned the chemical engine, and started out on a procession all over the Borough, a crowd quickly gathered, and soon about 200 men, women and children were in line, headed by the Stars and Stripes. They marched down South Street, and at the invitation of the rector, Mr. Brewster, into St. Michael’s church, where the people with deep emotion, sang together the Doxology and the national anthem, and gave thanks with grateful hearts that the long terrible years of conflict were ended at last. Out again on the Green, a bonfire was built, and while it was burning brightly impromptu speeches were made. The day dawned, soft and mellow, as a November day sometimes is. About seven o’clock there was a little let up for breakfast, but the bells never quite ceased ringing. The dignified village of Litchfield had a disheveled look on that morning, very unlike its usual trim appearance. Papers, confetti, the remnants of the bonfire littered the center and plainly showed that the town had been up all night celebrating. Refreshed by breakfast, every one who could get there, hastened to Bantam to join the parade. A band, provided by the forethought of W. S. Rogers led the procession, which included about sixty automobiles. Another pause came for the noon-day meal, then came the Litchfield parade, in which Bantam joined. The marchers were headed by Frank H. Turkington, and the Home Guard, the D. A. R., the Red Cross, the fire departments, the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts, the service flag of St. Anthony’s carried by young women, and many automobiles were in line, a coffin dedicated to the Kaiser was a special feature. Litchfield’s enthusiasm did not spend itself with these demonstrations, but finished the day with a patriotic “sing” on the Green in the evening, patriotic speeches and an appeal for the United War Work Campaign, which was then in progress.”

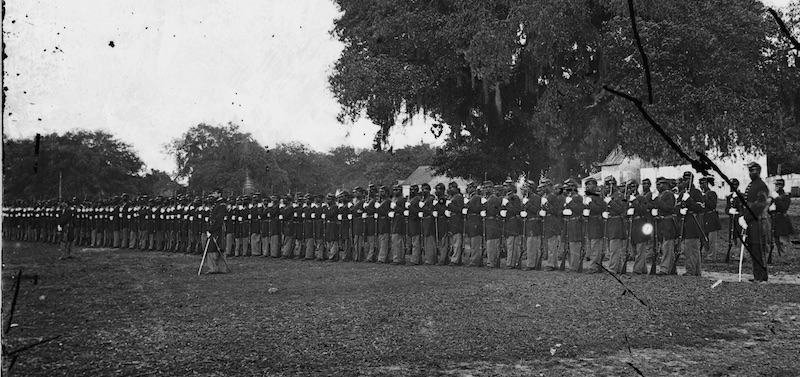

Amidst the understandable celebration, the town still mourned for its ten sons who died in the conflict. The sacrifices of these men were noted with a star next to their name on the town’s monument to its men who served in the World War. In many cases, those stars are now missing; in this centennial year of the Great War’s end, it seems appropriate for the town to repair this honor. But it is important to remember that these were men with lives and families, not just names on a plaque, deserving to be remembered for their sacrifices and experiences. They are:

Henry E. Cattey, who is often listed as being from the “Marsh District” of Northfield, but sometimes listed as being from Thomaston. He was a mechanic in Company I of the Sixth Infantry, and was killed in October 1918 while liberating the French town of Bois des Rappes in the first phase of the Meuse-Argonnes Offensive.

Roy F. Cornwell, who enlisted as a member of the New York State Militia from his father’s residence in Ellenville, but had lived in Litchfield for some time. He died on the ship en route to France.

Clayton Devines died of the Spanish Flu in November 1918 while at an army camp in Florida. Between 50 and 100 million people worldwide died of the epidemic.

Joseph Donohue – hometown unknown – was a student at the Connecticut Junior Republic who enlisted in the army and died in action on July 23, 1918, during a French and Americans advance on the Ourcq River.

August Guinchi of the 56th Regiment Coast Artillery was gassed was driving a tank. In a weakened condition, he succumbed to typhoid fever October 31, 1918.

Robert Jeffries died of pneumonia on January 20, 2018, at Camp Gordon, Florida.

Litchfield’s Morgan-Weir American Legion Post is named for Frank A. Morgan and James V. Weir, both of whom died in combat in World War I.

Frank A. Morgan was eager to enlist but was twice rejected from military service because he didn’t weigh enough. When the weight limit was lowered, Morgan became the first man from Litchfield to enlist. A corporal, he also became the first of Litchfield’s men to die in battle. His mother, Mrs. G. Durand Merriman, received a letter from her son’s commanding officer, providing details about his death: “Your son, Corporal Frank A. Morgan was killed June 20, 1918, near Mandres in the Toul sector. He was killed by the concussion of a shell; even though he died instantly, there was not a mark on him. . . . When we first went into the line he acted as a runner between the platoon and company headquarters and did his work so well that I proposed his name to the company commander as one to be made corporal at the first opportunity, and I am sure that had he lived he would have continued to win promotion. He is buried in an American Military Cemetery and the flag he fought for floats over his grave, while by his side are comrades who with him have paid the supreme price.”

Howard C. Sherry died of pneumonia on January 16, 1918, at Camp Johnston, Florida.

James V. Weir served in the 102nd Regiment alongside his brother, Thomas. Thomas provided the following account of his brother’s death at the Battle of Chateu Thierry: “At the start of the Chateau Thierry drive they went over the top at 5:30 A.M. and went into woods the other side of the starting position. They relieved the Marines, with Marines on left and French on right; the position was in a horse shoe. The company went ahead and had to wait for the French. They went back and went ahead again without barrage. Co. H. was in the 2nd batallion. Enemy artillery fire was very heavy, 2nd battalion in support, 3rd battalion ahead and 1st in reserve. The company was in open field kneeling down in close formation, a German big shell came over and landed 200 yards away. A piece landed beside the two Weir boys and hit James between the eyes. Roy Hotchkiss helped to carry out and bandage James, who was taken to the 103rd Field Hospital at La Ferte and buried there”.

Of Pio Zavotti, little is known except that he was born in Italy and was killed in action fighting for his adopted country.

Calm fell. From Heaven distilled a clemency;

There was peace on earth, and silence in the sky;

Some could, some could not, shake off misery:

The Sinister Spirit sneered: ‘It had to be!’

And again the Spirit of Pity whispered, ‘Why?’

– From Thomas Hardy, “And There Was a Great Calm”