Remains of the Whites’ Japanese tea house

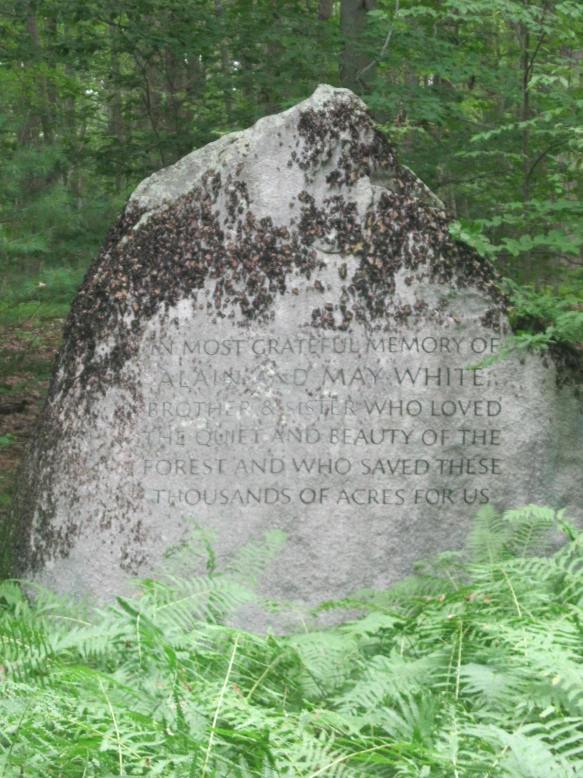

Many of the trails that wind through the White Memorial Conservation Center were originally constructed as carriage roads for Alain and May White. Great care was taken in building this network of roads, as evidenced by the many extant bridges, culverts, and drainage ditches. Carriage rides on roads carved out of forests was a popular leisure activity for wealthy Americans in the late 19th and early 20th century. The Rockefellers, for example, built 45 miles of carriage roads at Kykuit, their Tarrytown, New York, estate, eighteen miles or roads at their Forest Hill, Ohio, estate, and 57 miles in what is now Acadia National Park in Maine.

Beaver Pond overlook, White Memorial Foundation

Alain White oversaw the construction of dozens of miles of roads at Whitehall, what is now White Memorial. From the 1870 carriage house, the Whites would drive their team of horses around their property. Approximately four miles from their home was Beaver Pond. High above the pond they constructed a pull off so that they could admire the vista from their carriage. And on the shore of the pond, White built a Japanese tea house. Here Alain and May could entertain friends before returning back home.

Frederic Church, Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860

Wealthy Americans of this period were captivated by paintings by the likes of Frederic Church and Winslow Homer of the American wilderness and looked to have their own experiences in nature. And if that could be done by constructing a Japanese tea house on ground seemingly untouched by human hands, so much the better. At about the same time, Robert Pruyn, an Albany banker and businessman, constructed an entire estate with a Japanese theme on nearly 100,000 of Adirondack wilderness in Newcomb, New York. If on a smaller scale, Alain and May White were inspired by similar ideas in Litchfield and Morris.