The graves of Robert Lampman and William Elder stand side by side in Litchfield’s West Cemetery.

Memorial Day was originally Decoration Day, created in 1868 to lay flowers or wreaths on the graves those men who died in the Civil War. Tragically, that number was enormous; nearly 400,000 Union soldiers perished over the four years of the conflict. In setting aside May 30th, 1868, as the first Decoration Day, General John Logan, commander of the Grand Army of the Republic (the North’s largest veteran’s organization) declared: “We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. All that the consecrated wealth and taste of the Nation can add to their adornment and security is but a fitting tribute to the memory of her slain defenders. Let no wanton foot tread rudely on such hallowed grounds. Let pleasant paths invite the coming and going of reverent visitors and found mourners. Let no vandalism of avarice or neglect, no ravages of time, testify to the present or to the coming generations that we have forgotten, as a people, the cost of a free and undivided republic.”

For decades, Logan’s call went unheeded for some Connecticut veterans. When the state put out a call for African American volunteers in 1863, over 1,600 responded. The first 1,200 formed the 29th Connecticut Infantry, while the other 400 became the 30th Connecticut. It is interesting to note that not all of these men were Connecticut residents; as Massachusetts was the only other northern state accepting African American enlistees at this time, volunteers joined the Connecticut regiments from across the Northeast.

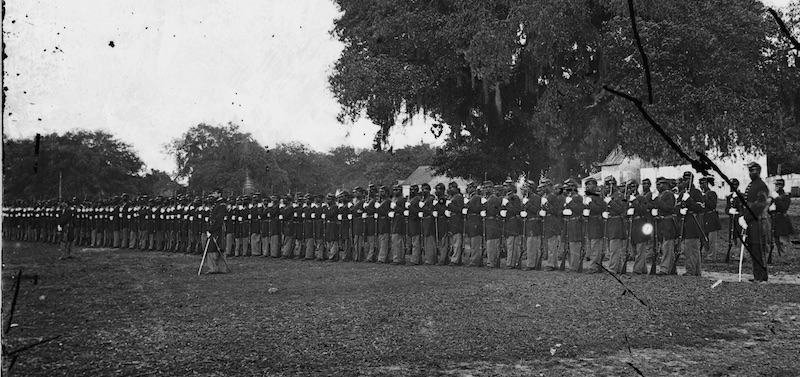

The volunteers that formed the 29th Connecticut trained in the Fair Haven section of New Haven and were mustered into the service of the United States in March 1864. Among these 1,200 were James Lampman and William Elder, who lived in Litchfield after the war; dozens of men from Litchfield County also enlisted in the regiment. In early April 1864, the unit was sent to Beaufort, South Carolina, where the above photograph was taken. For the next four months, the regiment drilled and served on picket duty before being sent to the Richmond theater in August. There it was involved in many engagements in the war’s final year. Thomas McKinley, a white officer serving in the regiment, was mortally wounded outside Richmond on September 24th. He is buried in Litchfield’s East Cemetery. The 29th suffered their most significant casualties at Kell House, near Richmond, on October 27, 1864, when 14 men were killed at 69 wounded. When Richmond fell to Union forces in early April 1865, the 29th Connecticut was the first Union infantry regiment to enter the Confederate capital. After Lee’s surrender, the men of the 29th dispatched to duty in Texas and Louisiana.

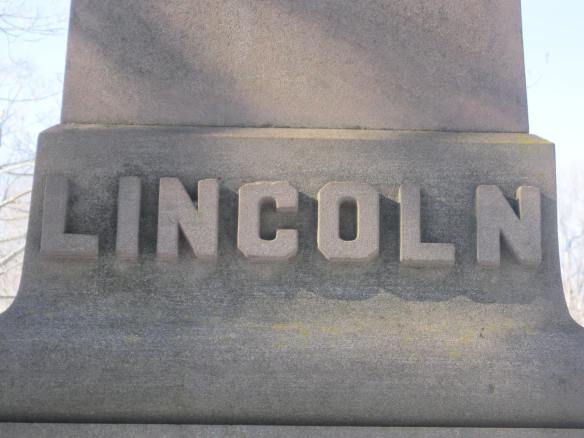

The 29th Connecticut monument in New Haven

When the war ended, the survivors attempted to return to a normal life. Many, however, were disabled from debilitating wounds or sickness. Many widows of men from the 29th had difficulty getting pensions because the required paperwork – notably marriage certificates – were rare in the African American community. While there were integrated Grand Army of the Republic posts, many were segregated, while African American veterans were blackballed from membership in still other posts. And while monuments were constructed across Connecticut to the state’s white regiments, no monuments were built to honor the state’s African American veterans until one was erected in Danbury in 2007. The following year, the men of the 29th were honored with a monument in New Haven.

For more information on the 29th Connecticut, see ProjeCT29, a website built and maintained by my students: https://pvermilyea.wixsite.com/29thconnecticut