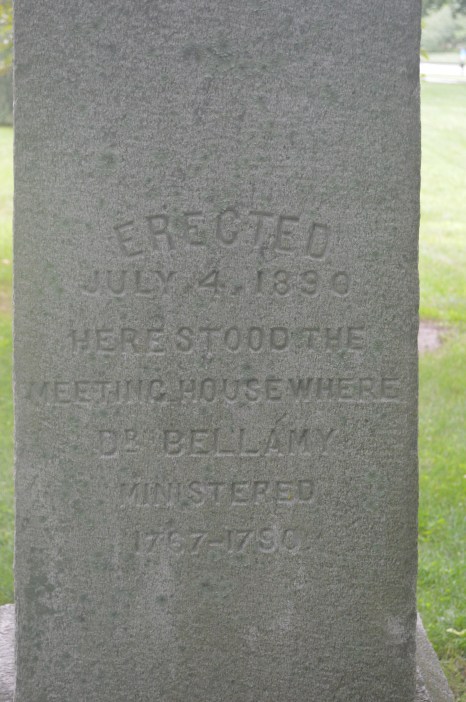

This monument, difficult to see as cars speed along Route 109 in Morris, marks the site of the King Family Grist Mill. The grist mill was once a vital part of New England communities. While we usually associate grist mills with grinding wheat into flour, that was not typically the case in New England. Here, with our rocky soil, it was far more common for farmers to raise rye, corn and buckwheat to be milled. In fact, white bread was considered to be a luxury.

This monument, difficult to see as cars speed along Route 109 in Morris, marks the site of the King Family Grist Mill. The grist mill was once a vital part of New England communities. While we usually associate grist mills with grinding wheat into flour, that was not typically the case in New England. Here, with our rocky soil, it was far more common for farmers to raise rye, corn and buckwheat to be milled. In fact, white bread was considered to be a luxury.

An undated image of King’s Grist Mill. Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society.

This particular grist mill, likely built in the 1830s, was initially run by the Loveland family, who operated the mill in Morris (then called South Plains) for nearly fifty years before it was taken over by the Kings. In addition to grinding grains, the families also utilized water power to saw timber and for the fulling (cleaning)of cloth. The mill was described by Marilyn Nichols (who wrote its history, likely around 1905) as being “one of the old landmarks and one of the more generally known throughout Litchfield County and other sections of the state.” Nichols described its location as being “in one of the most romantic and beautiful valleys of Connecticut.” In fact, Nichols wrote of one local artist who gained distinction – and $400 – by selling a painting of the mill at a New York studio.

Diagram explaining the workings of a grist mill. Courtesy of National Park Service.

The Loveland/King mill utilized two circular stones to grind. Traditionally, both stones would have grooves cut into them to act as teeth. The grains would be poured over the bottom stone while water power was used to turn the top stone, grinding the grain into flour. One bushel of grain typically yielded 35 pounds of flour. Johnnycake was the most expensive product of the mill, as it required a special bolt made from silk, and it was a particular target of hungry mice.

The milldam for the Loveland/King grist mill was destroyed to help create the Wigwam Reservoir for the city of Waterbury.

Farmers would bring their grains to the mill, and the milling usually took place while the farmer waited. The Lovelands were known to operate their mill until midnight to accommodate the farmers. Millers usually received a percentage of the grain as payment, and mills often served as commodity houses where grains and flour were traded.

Elijah King took possession of the grist mill sometime before 1874, and while he ran it successfully for some years, changes in farming techniques and the decline of old milling practices left him bankrupt. In fact, the prevalence of wheat flour from the Midwest and the advent of gasoline-powered engines to mill grains on the farm for animal consumption prompted Nichols to write, “obsolete is the old grist mill in Connecticut.” Few remnants of grist mills are visible in the state, and the only trace of the Loveland/King mill, once a vital part of the local economy in Litchfield County, is the marker placed by the King family along Route 109.

Elijah King took possession of the grist mill sometime before 1874, and while he ran it successfully for some years, changes in farming techniques and the decline of old milling practices left him bankrupt. In fact, the prevalence of wheat flour from the Midwest and the advent of gasoline-powered engines to mill grains on the farm for animal consumption prompted Nichols to write, “obsolete is the old grist mill in Connecticut.” Few remnants of grist mills are visible in the state, and the only trace of the Loveland/King mill, once a vital part of the local economy in Litchfield County, is the marker placed by the King family along Route 109.

Update: Below are two maps depicting the mill. The first is Clark’s 1859 map designating the mill as Loveland’s mill. The second is Beers’ 1874 map, showing that King owned the mill at that point. Note also the numerous structures in the area compared to today.

Clark’s 1859 map

Beers’ 1874 map. Thanks to Linda Hocking of the Litchfield Historical Society for supplying the images of these maps!

Much of this information came from Marilyn Nichols’ lecture, available at: “Old Grist Mills Cease” (2010-367-0) Litchfield Historical Society, Helga J. Ingraham Memorial Library, P.O. Box 385, 7 South Street, Litchfield, Connecticut, 06759

41.672976

-73.153416

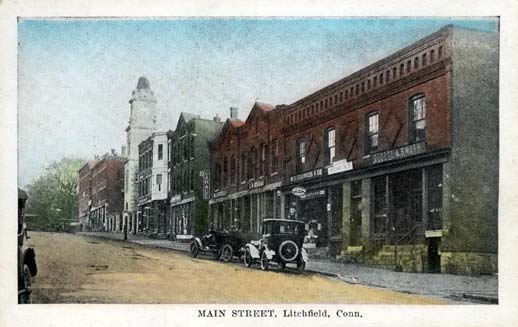

2013 marks the 100th anniversary of the Litchfield Garden Club. On September 9, 1913, nine women from the Litchfield area met at the home of Edith and Alice Kingsbury on North Street and organized the club, with annual dues of two dollars. S. Edson Gage, an architect who had designed the Litchfield Playhouse that stood at the site of the current town hall, was elected president.

2013 marks the 100th anniversary of the Litchfield Garden Club. On September 9, 1913, nine women from the Litchfield area met at the home of Edith and Alice Kingsbury on North Street and organized the club, with annual dues of two dollars. S. Edson Gage, an architect who had designed the Litchfield Playhouse that stood at the site of the current town hall, was elected president.