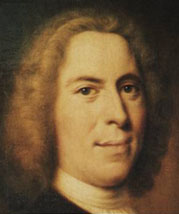

Some legends become carved in stone, or, in the case of Woodbury’s milestone, cast in iron. The small plaque accompanying a milestone along Main Street in Woodbury states, “Benjamin Franklin Mile Stone.” The milestone itself reads “XIV M,” or fourteen miles. While there is a long-standing tradition that Franklin had these markers laid out – sometimes the legend even states that Franklin himself was involved in the placement of the stones – he was almost certainly not involved.

Certain facts about the legend are true. Franklin did serve as one of two deputy postmasters general for the British colonies from 1753 to 1774. Franklin did oversee the modernization of postal roads during his tenure. And, the cost postage in that era was calculated by distance. However, there is no evidence in Franklin’s papers to corroborate the story, and while Franklin did serve as deputy postmaster general for 21 years, he was actually in the American colonies for only 6 years. The rest of the time he was in England on business representing the Pennsylvania colony.

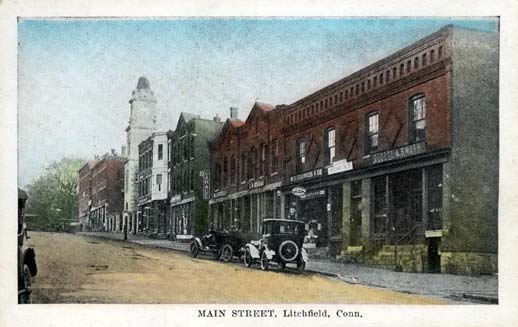

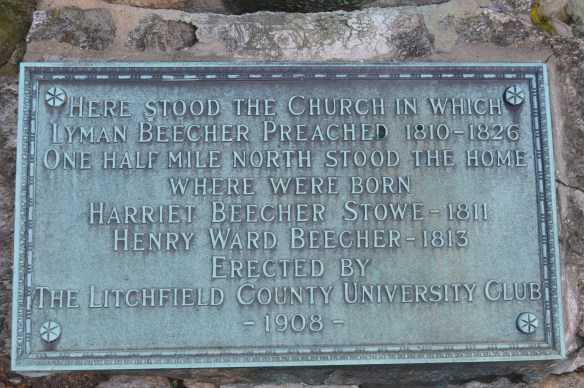

A specific aspect of the legend claims that Franklin erected a series of milestones between Woodbury and Litchfield while on a trip to New England from June to November 1763. However, Franklin not only didn’t set foot in Connecticut on that trip, but neither Woodbury nor Litchfield had a post office at the time.

Milestones had little to do with postal operations, being mostly “embellishments” set up in towns to aid passersby. Post riders were quite familiar with their routes, well aware of the mileages between different points. Still, there are mysteries surrounding the milestones. If it wasn’t Franklin, who did put them up? The series of milestones seems to be the work of different people, done at different times. And what does the distance relate to? Along modern Route 6, it is thirteen miles from Woodbury to both Thomaston and Newtown. Perhaps further study will reveal who constructed the milestone, and for what destination.