It’s easy to miss. Traveling past Litchfield Bancorp on Route 202, the modern motorist is often too concerned with navigating traffic to notice the small marker on the bank’s lawn. However, when it was erected 225 years ago, travelers only as fast as their horse or feet could take them almost certainly saw the engraved stone:

33 miles to Hartford

102 miles to New York

J. Strong AD 1787

It remains today, a reminder of the ingenuity of early Americans as well as one Jedediah Strong, one of Litchfield’s more unusual characters.

Roman milestone

Milestones have existed since at least Roman times, and dozens of milestones – bearing the name of the emperor under who rule they were erected and the distance to Rome – remain scattered across what was once the Roman Empire. Milestones serve to mark the route and distance to a site. As such, they provided reassurance a traveler that he was on the right road, and gave him an idea of how much longer his journey would last.

Franklin’s odometer

In our age of satellite navigation and laser-guided surveying, it is interesting to ponder how these measurements were made in a much simpler time. Assuming that Jedediah Strong measured these distances himself, he likely did it by attaching an odometer to one of the wheels of his wagon. The Romans possessed this technology, but like many of their innovations, it was lost as Europe entered the so-called Dark Ages. The technology was rediscovered by Benjamin Franklin who, as Postmaster General, was desirous of knowing the shortest routes for sending the mail. His odometer kept count of the number of revolutions made by the wagon wheel; by multiplying the number of revolutions by the circumference of the wheel, he arrived at the distance traveled. (Incidentally, Google Maps states that the distance from Strong’s milestone to Hartford is 33.1 miles, and to the Bowling Green in Manhattan is 101 miles, testimony to the accuracy of the odometers of the time.)

Jedediah Strong was born in Litchfield in 1738, and graduated from Yale College in 1761, making him the second Litchfield resident with a college degree. Like many of his era, he studied divinity but, perhaps inspired by the tumult of growing opposition to Britain, turned to law and politics. He served as a selectman of Litchfield and town clerk, as a state judge and representative, and as a member of the Continental Congress and the Connecticut convention to ratify the Constitution.

Of Strong, one writer commented, “a diminutive figure, a limping gait, and an unpleasant countenance were, however, in some measure atoned for by a certain degree of promptness and tact in the discharge of public business.”

When the Revolution broke out, Strong donated a gun, bayonet, and a belt that was carried into war by William Patterson, and a second gun that was carried by Benjamin Taylor. In 1780, at the peak of his political powers, Strong welcomed Noah Webster as his student. He also served as the driving force behind Litchfield’s first Temperance Association.

Tapping Reeve

His life soon took a dramatic turn. Strong’s first wife, Ruth Patterson died after giving birth to a daughter and, in 1788, the widower married Susannah Wyllys, daughter of Connecticut’s Secretary of State. Less than two years later Strong was arrested and brought before judge Tapping Reeve. Accused of beating his wife, pulling her hair, and kicking her out of bed, Strong also allegedly “spit in her face times without number.” Reeve granted Susannah an immediate divorce, and required Strong to post a 1,000 pound surety. His career collapsed, and Strong increasingly turned to alcohol. He was soon on public assistance, and when he died on August 21, 1802, at the age of 64, he was buried in the West Cemetery without a stone.

Despite these travails, Strong’s milestone remained, serving passersby for more than two centuries. Still, the modern explorer is left to ponder, why did he build it in the first place? We might speculate that it was perhaps his interpretation of his civic duty, or that he was looking to boost Litchfield’s commercial prospects. Regardless, the stone has been a silent witness to most of the town’s history.

41.745823

-73.202393

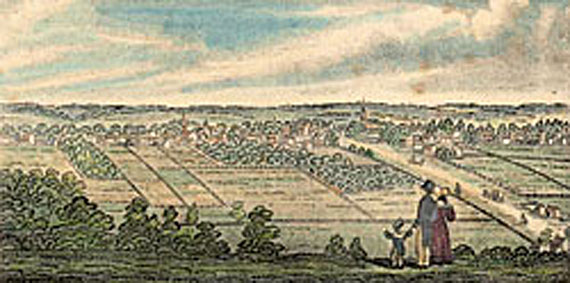

Such is the case with Northfield’s Knife Shop Road. Here, on the Humiston (or Humaston) Brook mill pond, once stood Litchfield’s largest business.

Such is the case with Northfield’s Knife Shop Road. Here, on the Humiston (or Humaston) Brook mill pond, once stood Litchfield’s largest business. The Northfield Knife Company was established in 1858, taking advantage of the water power and access to the Naugatuck Railroad. In the post-Civil War era the company produced over 12,000 knives per year.

The Northfield Knife Company was established in 1858, taking advantage of the water power and access to the Naugatuck Railroad. In the post-Civil War era the company produced over 12,000 knives per year. It employed 120 workers, many of whom were highly trained experts from Sheffield, England, then world-renown for its excellence in steel-knife production. (In fact, when a proposal was made in 1866 to incorporate Northfield as a separate town, one opponent argued before the state legislature that the English cutlers weren’t fit to be citizens of a town!)

It employed 120 workers, many of whom were highly trained experts from Sheffield, England, then world-renown for its excellence in steel-knife production. (In fact, when a proposal was made in 1866 to incorporate Northfield as a separate town, one opponent argued before the state legislature that the English cutlers weren’t fit to be citizens of a town!) Northfield knives live on as Northfield UN-X-LD, a division of Great Eastern Cutlery. Today they are made in Titusville, Pennsylvania. The mill pond in Northfield remains, however, testimony to the industrial heritage of this area and to the Northfield Knife Company, an internationally-known business whose knives were featured at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Northfield knives live on as Northfield UN-X-LD, a division of Great Eastern Cutlery. Today they are made in Titusville, Pennsylvania. The mill pond in Northfield remains, however, testimony to the industrial heritage of this area and to the Northfield Knife Company, an internationally-known business whose knives were featured at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.