Connecticut Highway Department marker near the Gooseboro drive-in in Bantam.

There are among the most ubiquitous markers on our man-made landscape. Usually between twelve and eighteen inches high, they are simple stone blocks engraved with the initials “CHD.”

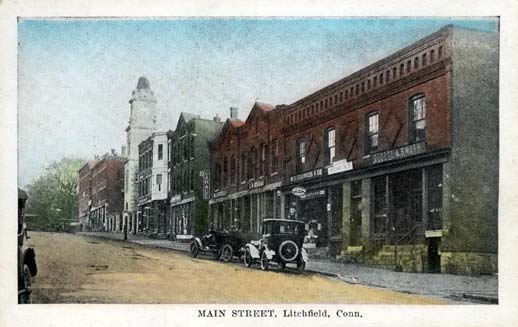

A Connecticut Highway Department marker alongside Route 4 by the Torrington Country Club,

“CHD” stands for the Connecticut Highway Department, a state agency that was incorporated into the Department of Transportation in 1969. At one time, however, it was responsible for the construction and maintenance of all state roads.

A Connecticut Highway Department marker abuts the sidewalk on the west side of South Street in Litchfield.

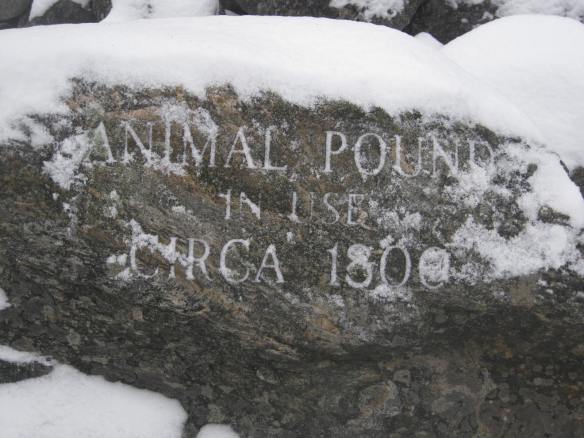

The Connecticut Highway Department began preparing highway boundary maps in 1926; much of the work was completed by the Works Progress Administartion during the Great Depression. These maps were done in accordance with a statue passed in 1925 that required that the “Highway Commissioner … mark such boundary limits by a uniform and distinctive type of marker.” The stone “CHD” markers satisfy this requirement.

Three Connecticut Highway Markers denote the right of way to widen the turn along the northeast corner between the middle and eastern sections of the Litchfield Green. One marker is visible at the extreme right of the photo; a second is partially hidden by the tree at the front right; the third is visible between the telephone pole and tree in the background.

The highway department was originally created specifically to build highways. By 1923, however, its tasks had expanded to eliminating dangerous conditions on roads, improving the roadsides, installing proper warning signs, removing snow and ice from the highways, and – pertinent to these markers – establishing boundary lines alongside the highways and securing the rights of way for the purpose of widening and straightening roads.

To oversee these last two tasks, the Connecticut Highway Department created the Bureau of Highway Boundaries and Rights of Way. The bureau had three major tasks: land titles, boundary surveys, and right of way purchases. When it was determined that a new road needed to be built, the bureau conducted a title search, acquired the property and was charged with “properly marking the boundaries of all state roads” (Forty Years of Highway Development in Connecticut, 16). The result of this, of course, are the thousands of stone markers that dot Connecticut roadsides.

The stone “CHD” markers have interesting stories to tell to those explorers willing to look into them. The “CHD” marker above is on Prospect Street, a town road, not a state road, However, a look at an old map shows that this was once the site of “Wolcott Road.” While this road was subsequently closed, the right-of-way is still maintained by the state.

These stone markers are a thing of the past, however. Today, the Connecticut Department of Transportation marks its property flush to the ground, with bronze discs engraved with “CTDOT.”

41.714589

-73.263748