John Johansen, 1916-2012

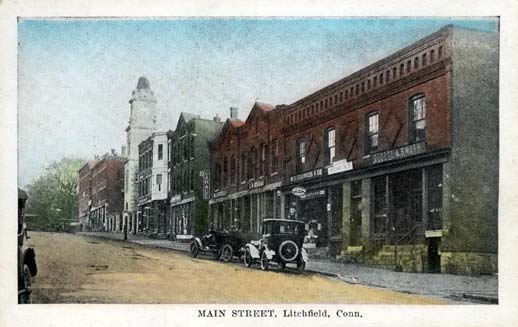

For many, the thought of a road race through Litchfield conjures images of colonial homes, painted white with black shutters. While the center of the town is dominated by colonial – and colonial revival – architecture, runners entering the third mile of the Litchfield Hills Road Race course become aware that the town also has important examples of modern architecture.

Litchfield Intermediate School (the orange and yellow sections are later additions)

To the left just as runners pass the two-mile mark to enter the race’s third mile is the Litchfield Intermediate School, designed as a junior high school in 1965 by John Johansen. Johansen – who along with Marcel Breuer, Landis Gores, Philip Johnson and Eliot Noyes was one of the “Harvard Five,” students of the noted Walter Gropius – had earlier designed the Huvelle House on Litchfield’s Beecher Lane. Noted for his individualist style, Johansen built the school into the side of Plumb Hill, and designed it with four main sections, an administrative heart along with a gym, auditorium, and classrooms. The school is particularly notable for its courtyards.

Litchfield High School, designed by Walter Gropius in 1954-56.

Over the right shoulder of runners entering the third mile is Litchfield High School, designed a decade earlier by Marcel Breuer (another of the Harvard Five), and containing a striking gymnasium inspired by Walter Gropius, Johansen’s teacher and father-in-law and one-time director of the Bauhaus school. Additions have obstructed the dramatic side view of the gym as originally designed, but the wall of glass remains striking.

Marcel Breuer’s Gagarin I, built on Gallows Lane between 1956 and 1957.

Eliot Noyes’s addition to the Oliver Wolcott Library.

While runners grappling with Gallows Lane and the race’s final mile aren’t necessarily looking for modern architecture, two outstanding examples await. Breuer’s Gagarin I and II, while scarcely visible from the road, offer sweeping vistas to the west. Eliot Noyes, yet another member of the Harvard Five, offered a modern addition to the Oliver Wolcott Library that complements the original 1799 structure.

For more on Litchfield’s architectural history, see Rachel Carley’s outstanding book, Litchfield: The Making of a New England Town.

For more information on the history of the Litchfield Road Race, see Lou Pellegrino’s forthcoming book A History of the Litchfield Hills Road Race: In Smallness there is Beauty. (Available May 2016)