Tucked into a tree in Litchfield’s East Cemetery is a marker commemorating the life of Frederick Asa Bacon, who was born in Litchfield in 1812. His father attended the Litchfield Law School, and he, his mother and two brothers attended the Litchfield Female Academy. A voyage to England in 1829 sparked an interest in a life at sea, and he joined the United States Navy as a midshipman in 1832. In 1838, while serving as a passed midshipman – one who has passed the examination to be a lieutenant but is waiting for a vacancy at that rank – Bacon was one of two officers named to command the U.S.S. Sea Gull, a schooner that was part of the United States Exploring Expedition (known as the US Ex Ex).

The U.S.S. Sea Gull, in distress of Cape Horn. A drawing by Alfred Thomas Agate, a member of the U.S. Ex Ex

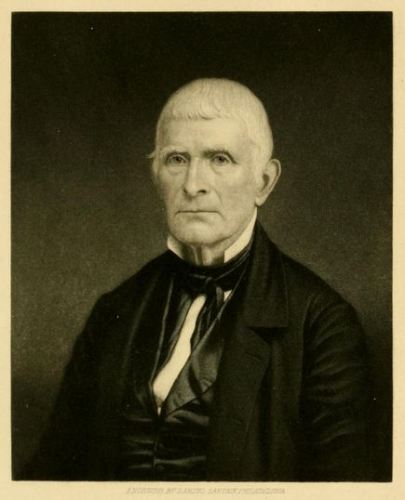

The US Ex Ex was one of several 19th century voyages of discovery sponsored by the United States government. Under the command of Charles Wilkes, this expedition was sent circumnavigate the globe in order to search for the magnetic south pole, map the western coast of North America, and explore the islands of the south Pacific. Bacon’s Sea Gull was formerly a New York harbor pilot boat called the New Jersey. Wilkes included two schooners in his six-ship squadron because he believed the agility would be highly prized in the ice around the South Pole.

The ships left Norfolk, Virginia, on August 18, 1838, bound for the tip of South America. There they would survey and collect specimens before making a February (summer in the southern hemisphere) exploration of the Antarctic. Enormous icebergs – some reportedly as big as the United States Capitol – and huge waves caused Wilkes to order the Sea Gull out of danger in search of scientific equipment left behind on Deception Island by an earlier British expedition. The crew did not find the thermometer, but did determine that Deception Island was an active volcano.

Memorial to the men who died during the U.S. Ex Ex in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA. Courtesy of findagrave.com

By mid-April, Wilkes ordered part of the squadron to sail for Valparaiso, Chile, while the Sea Gull and her sister schooner Flying Fish waited for a supply ship. While the latter vessel arrived in Chile by mid-May, there was no sign of the Sea Gull, which was last seen waiting out strong winds at Staten Island off the coast of South America’s Cape Horn. When after a month the Sea Gull still had not arrived, the officers of the Ex Ex assumed that she was lost; Wilkes later speculated that in the gales off Cape Horn, the schooner might have tripped her foremast, which would have ripped up the foredeck and made her unseaworthy. A collection for a monument in memory of the ship’s crew was taken up by the expedition’s officers; the monument still stands in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Ex Ex continued on its voyage, achieving the first sighting of the Antarctic continent, making invaluable maps of the South Pacific islands and the currents off the American Pacific coast, and gathering enormous numbers – in excess of 60,000 – specimens of birds, fish, plants, and shells. These specimens would later form the backbone of the Smithsonian Institution. At least five books were published on the scientific and maritime discoveries of the expedition.

Captain Charles Wilkes would become embroiled in controversy for his actions during the expedition, and in fact when Lieutenant Robert Pinkney brought court martial proceedings against Wilkes, the commander criticized his accuser by contrasting “the intelligence, attention to duty, and untiring activity of the lamented Reid and Bacon with all that is opposite in the character of Lieutenant Pinkney.”

Bacon was remembered by Wilkes as “among the most promising young officers in the squadron.” Lieutenant Reynolds of the expedition highlighted the Bacon’s personal tragedy by remembering,“Poor, poor fellows, what a terrible lot. The two officers were young men of my age, one if he indeed be gone, leaving a wife more youthful than himself and a child that he has never seen.”

For more information on the Sea Gull and the U.S. Ex Ex, see Nathaniel Philbrick’s book, Sea of Glory.