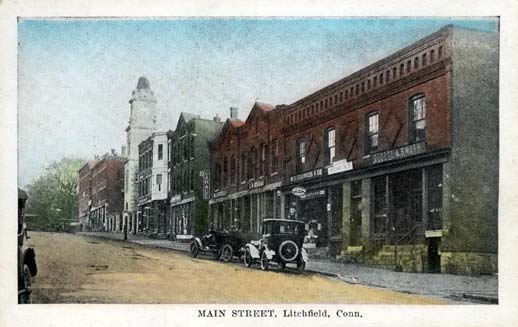

We take to the woods for many reasons. Thoreau famously wrote, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” Most of us take to the woods for less philosophical reasons – to hike, run, snowshoe, mountain bike, or bird watch. Hidden amongst the Litchfield woods, however, are reminders of the way the land was used in the past.

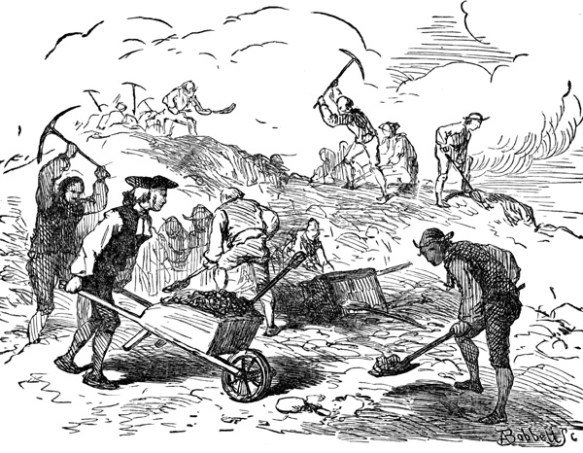

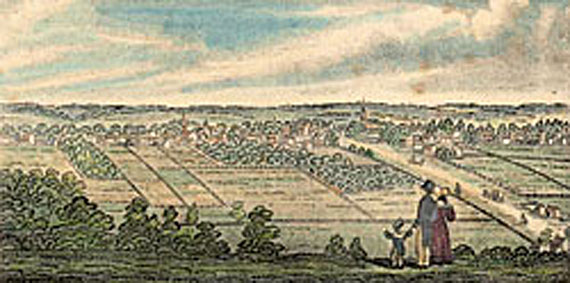

There is little old growth forest left in Litchfield County. In the southern environs of the county the land was cleared for farms. In its northern reaches, Litchfield County’s woods were utilized for the charcoal needed to power iron furnaces. When these industries began to transform or fade away, the forests reclaimed their original territory, engulfing many man-made objects and alterations to the landscape.

Perhaps this is most true of the White Memorial Foundation, which owns approximately 5,000 acres in Litchfield and Morris. In these woods remain many implements of the county’s agricultural and industrial past.

One fascinating example is the base on which the White family’s windmill once stood. The explorer can find it on the appropriately named Windmill Hill, very near the White Memorial visitor center and museum. The proximity is no coincidence.

John Jay White, whose children established the foundation in the early 1900s, was a New York real estate magnate who moved from 5th Avenue to Litchfield in 1863. The home he built, Whitehall, in many ways epitomized the Victorian architectural fashion popular at the time.

On the top of a nearby hill White had a cistern built. A nearby windmill pumped water into the covered cistern. Pipes then brought the water more than a quarter mile to the house, which thus enjoyed natural water pressure.

Today, a concrete slab marks the site of the cistern. A concrete structure stands nearby; it was built to house the electric pump that replaced the windmill but was rendered obsolete a number of years ago when a new well was dug.

Whitehall still stands, albeit in modified form, as the visitor center and museum of the White Memorial Foundation. Its top floor was removed and modifications made that erased the structure’s Victorian elements. Only in the carriage house are glimpses of the Victorian splendor that once marked the estate evident.