The first Arbor Day was held on April 10, 1872 and became an international event eleven years later when Birdsley Northrup of Kent, Connecticut, introduced the event to Japan. However, Theodore Roosevelt’s ascendency to the presidency in 1901 and his emphasis on conservation issues sparked a nationwide surge of interest in Arbor Day.

In 1902 the Mary Floyd Tallmadge Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution celebrated the first Arbor Day of Roosevelt’s presidency by planting a tree on the Litchfield Green to commemorate the services of the town’s Revolutionary War soldiers.

In all, 507 men from Litchfield served the Patriot cause between 1775 and 1783. The first to serve were the men of the company led by David Welch of Milton, who were called up soon after news of Lexington and Concord arrived. A second company enlisted in January 1776 to serve for the defense of New York City. They drafted a contract specifying the terms of their service under Major General Charles Lee, stating that they were convinced of “the Necessity of a body of Forces to defend against certain Wicked Purposes formed by the instruments of Ministerial Tyranny.” They specified, however, that they would not serve for more than eight weeks, and stated that General Lee had “given his Word and Honor” to uphold these terms.

In November 1776 another company of Litchfield men under Captain Bezaleel Beebe set off for New York. Thirty-six handpicked men of the company under Captain Beebe were sent to reinforce the American garrison at Fort Washington (today the Manhattan end of the George Washington Bridge). The men marched into a trap, and were forced to surrender with the entire 2,600 man garrison of the fort. Although the men were exchanged about a month later, only 11 of these men made it home to Litchfield.

In March 1777 a new call for troops went out, and Litchfield was tasked with enlisting 92 of its men. The town voted to pay 12 pounds per year to each soldier and to supply “necessaries” to each soldier’s family. A final call for troops reached town in 1781, and a “selective draft” took place, in which the town was divided into three classes and each class was expected to raise a certain number of men.

In addition to those men who were killed and wounded in battle, twenty Litchfield men died while on the dreaded British prison ships.

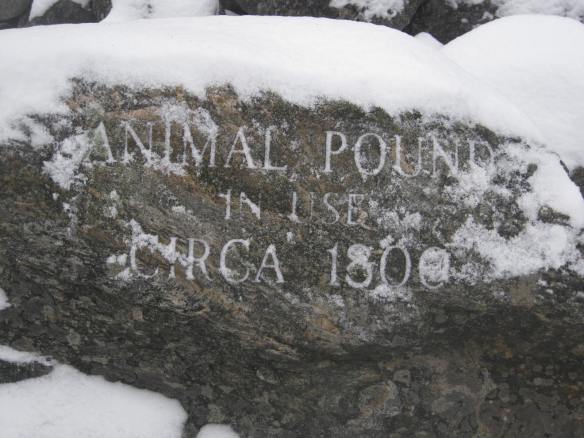

Today, a small stone marker stands at the foot of the tree dedicated to these soldiers. Its faded inscription reads:

Planted in Memory of

Litchfield’s Revolutionary Soldiers

by the

Mary Floyd Tallmadge Chapter

DAR

Arbor Day 1902